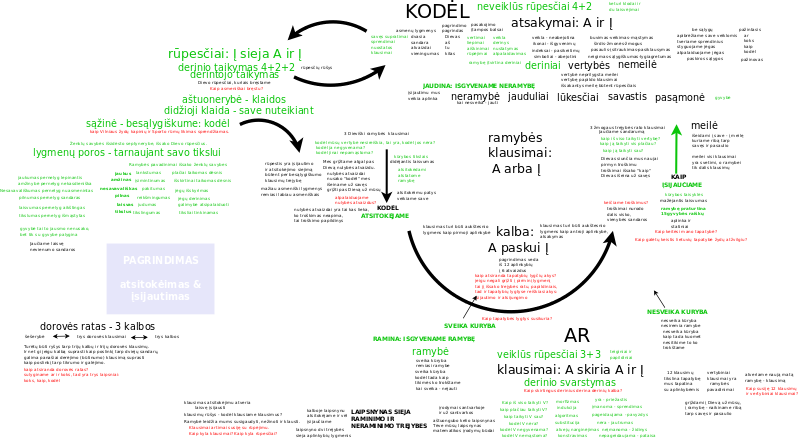

Žr. Dorovė, Dorovės tyrimas, Dorovė gyvenime, Elgesys, Dorovės sąvokos, Dorovės pavyzdžiai, Klaidos, Gyvenimo būdas ir stilius

Ieškau raktų į dorovę.

Dorovei svarbias keturias vienumos sampratas pristačiau pranešime, Lietuvių ir litvakų šimtametis vaidas, 1940-2040 m. Dorovinis tyrimas.

Kaip turėtumėme elgtis?

- Ar, ką, kaip, kodėl amžinai bręstame?

- Kaip žmogus dorove atsisako savęs?

Kodėl turėtumėme veikti?

- Kas mums svarbu?

- Kas mums svarbiausia ir kodėl?

- Kaip dorovė ima rūpėti?

- Kokie išminties pamokymai?

- Susieti dorovės rėmus ir gėrio kryptis.

- Poreikiais pagrįsti dorovės rėmus, kaip įvairiai suprantame gerumą?

- Kaip žmogus susigaudo, jog reikia keisti kryptį?

- Kokios mūsų vertybės?

- Jeigu tikslas yra gyventi nežinojimu, ar mes turėtumėme didinti savastį (labiau įsijausti) ar mažinti savastį (atsitokėti)?

Kaip turėtumėme veikti? Koks mūsų pasirinkimų malūnas?

- Kaip žmogus susigaudo jog reikia keisti kryptį? Ieškok nulybės atvaizdų ryšio su nežinojimo keliu.

- Kaip mus veikia aplinka ir kaip ją veikiame?

- Kaip pasąmonė išplečia sąmonę?

- Kaip atmintis išplečia protą?

- Kaip kalbos tveria atmintį ir sąvokas?

- Kaip mus įtakoja mūsų pažįstami, pavyzdžiui, kad naudotumėme svaigalus?

- Kaip bręstame?

- Kaip žmogus susigaudo jog reikia keisti kryptį?

- Kokia sąmoningumo lygmens svarba?

- Kokie dorovės dėsniai? Juos rinkti.

- Kaip Dievas vis naujai iškyla žmogaus elgesyje?

Ką turėtumėme veikti?

- Kaip mums būti viena?

- Kaip įsipareigojame būti viena?

- Kaip mums būti viena?

- Kaip esame viena?

- Kaip renkamės gyventi visais ir ne tik savimi?

- Kaip mus veikia aplinka ir kaip ją veikiame?

Ar mums veikti: Kas yra blogis?

- Kokios sandaros ir sąvokos grindžia dorovę?

Kas mums trukdo veikti ką turėtumėme?

- Kaip Dievas įprasmina blogį, išardo, pritaiko ir sieja su gerumu?

- Ar gali žmogus ar būtybė žinodami tyčia rinktis blogį sau ar kitam? Tyčia rodyti blogą valią? Kaip ir kodėl?

Tiriu: Atsakomybė Pamokymai

Sąmonė - dorovė

Dorovės klausimas: Kaip žmogus turėtų elgtis?

- Kodėl derėtų veikti?

- Kaip derėtų veikti?

- Ką derėtų veikti?

- Ar derėtų veikti? Dorovės atsakymas: Žmogus jau veikia

Dorovės esmė

Dorovė yra sąmoningumo išreikalavimas, tad ja mes patys sąmoningėjame.

Dorovės esmė yra mūsų privalėjimas atsiverti, sąmoningėti, puoselėti ryškesnį sąmoningumą, užtat amžinai bręsti ir atsiskleisti. Dorovė reiškiasi mūsų pasirinkimais:

- Esant apimčiai, sąlygoms, besąlygiškai rinktis išeiti už savęs, už apimties, vietoj kad trauktis gilyn į save.

- Lyginant dvi apimtis, dvi sąlygas, rinktis platesnę apimtį, labiau skiriančią sąmonės nežinojimą ir pasąmonės žinojimą.

- Atsitokėti, pereiti iš Koks į Kaip.

Santykinė, sąlyginė dorovė - vienumo sampratų lyginimas - nusistatymų vertinimas

- Dorovė yra vidinis nusistatymas, metafizinis nusistatymas. Nedoras nusistatymas - manyti, kad mes visi esame skirtingi žmonės. Doras nusistatymas - esame vienas žmogus skirtingose aplinkybėse. Dorovinis iššūkis - kaip priimti valių daugybę. Atjauta yra tam naudinga priemonė tačiau nebūtinai ir gal neesmingai.

Dorove sąmoningėjame - renkamės gyventi

Atsiplėšiame nuo savo sąlygų

- Skiriame ką žinome ir ko nežinome.

- Atsisakome savęs. Gyvename bendriau.

- Atpažįstame save. Skiriame sąmonę ir pasąmonę.

- Gyvename nežinojimu. Taip renkamės. Susitelkiame į nežinojimą.

- Gyvename sąmoningai. Sąmoningai išgyvename save.

Susigaudome, renkamės platesnę apimtį, sąmoningėjame

- Suvokiame, kad nesuvokiame. Skiriame suvokimą ir nesuvokimą.

- Suvokiame, kad už mūsų gali būti kažkas daugiau, tad galime ir turime gyventi viena, gyventi visais, gyventi Kitu.

- Prisiimame atsakomybę už tą tarpą tarp sąmonės ir pasąmonės, kuriame gyvename.

- Tiriame, kaip meile palaikome gyvybę.

- Susigaudome, jog būtent mes "turėtumėme" būti geri. Būtent mes galime būti geri, nes Dievas nebūtinai geras. Dorovė taikytina būtent mums, ne Dievui. Dievas ir gerumas būtent mums būtini.

Ugdome sąmoningumą - sąmoningai puoselėjame pasąmonę, kad ji palaikytų sąmonę

- Suprantame, kad esame netikslingi, netobuli. Skiriame kaip elgiamės ir kaip turėtumėme elgtis.

- Pasižiūrime į save.

- Tikriname save.

- Renkamės sąmoningumą - verčiau mokytis valios pagrindu - vertybėmis, nė širdies - lūkesčių; labiau širdies pagrindu nė proto - abejonių; labiau proto pagrindu nė kūno - poreikių.

- Dorove sąmonė puoselėja pasąmonę, kad ji atitiktų sąmonę ir ją palaikytų. Tobuliname pasąmonę sąmoningai gyvendami jos tveriama kertine vertybe, ją nuoširdžiai tikrindami, ryškindami, tikslindami. Širdingai gyvename savo vertybe, taip kad jinai mus atstotų, juk būtent ją galime tobulinti. Pasąmonę puoselėjame trejybės ratu, kada renkamės brandinti save.

- Save pakeičiame besąlygiška vertybe, kuria gyvendami galime mokytis ir ugdytis, kurią galime tikslinti.

- Ryškiname nežinojimą. Elgesį grindžiame nežinojimu.

- Išlaikome sąmoningumą.

- Laikomės nežinojimo kelio.

- Prisiimame atsakomybę, jog privalome patys susigaudyti, apsispręsti, rinktis - Dievas ir niekas kitas už mus tai nepadarys. Turime remtis savo nežinojimu.

Grindžiame Dievo būtinumą, sąmoningumo būtinumą

- Skiriame Dievo besąlygiškumą ir mūsų sąlygiškumą. Suvokiame savo laisvę, jos dievišką šaltinį mumyse.

- Išreikalaujame, kad Dievas būtų geras. Kartu išreikalaujame, kad jisai būtų. Išreikalaujame jo būtinumą. Ir patys esame tas Dievas, kuris "turėtų" būti. Gyvename Dievu. Tuo pačiu įgyvendiname vienumą.

- Puoselėjame šviesuolių bendrystę, kartu puoselėjame visų vienumą besąlygiškos tiesos pagrindu.

- Renkamės Dievą vietoj visuomenės. Galime savaip suprasti bendrą reikalą besąlygiškai kaip Dievo reikalą, ne sąlygiškai kaip kitų reikalą.

Ketverybės žmogiški lygmenys

- Žmogus yra tiktai dviejose apimtyse (kažkame ir betkame), o Dievas yra visose keturiose.

Kas yra dorovė?

Dorove yra mūsų pagrindas rinktis, kaip gyventi. Skiriame ką žinome ir ko nežinome; ką suvokiame ir ko nesuvokiame; kaip elgiamės ir kaip turėtumėme elgtis; kas besąlygiška - Dievo, ir kas sąlygiška - mūsų.

Dorovė išskiria sąmonę ir pasąmonę. Atsiplėšiame nuo savo sąlygų, nuo savo pasąmonės - gyvename sąmone.

- Dorovė yra išėjimas už sąlygų.

- Elgesio ir dorovės apibrėžimai labai priklauso nuo gyvenimo sąlygų, kaip plačiai suprantame gyvenimą. Užtat jeigu elgesį suprantame, kaip pasaulio apribotą, sąlygotą, tai dorovę galime suprasti, kaip išėjimą už tų sąlygų, jų nepaisymo, užtat elgesio praplėtimą. Pavyzdžiui, dorovė atsiranda kada įsivaizduojame mums skirtą kelią, o jeigu tokio neįsivaizduojame, tada jis mus niekaip nevaržo. Tad pirmiausiai tenka susigaudyti, kad gyvenime yra kelias, o paskui, kad reikia stengtis jo laikytis. Tenka susigaudyti, jog gyvenime renkamės ne šiaip.

- Deri atsisakyti sąlygų ir tik tada jų rinktis.

- Dorovės yra laikymasis nežinojimo kelio.

- Dorovė yra sugrįžimas į kelią - troškimo, laukimo, nežinojimo. Elgesys yra nukrypimas nuo kelio - į netroškimą, sulaukimą, žinojimą.

- Dorovė tad yra nukrypimas nuo nukrypimo. Mūsų dorovė yra, kad mes vis sugrįžtame į save, į savo gerą pradą.

- Tai primena Sokrato iššūkį Platono Valstybėje, parodyti jog net ir neteisingame pasaulyje (kuris kreivas, taip kad ištisai nuklystame, ir kuris teisina nuklydimą) dera gyventi teisingais (laikytis kelio).

- Tarpas yra skirtumas tarp nežinojimo ir žinojimo. Mūsų elgesį, susigaudymą ir dorovę reikia plėtoti tarpo pagrindu, ką jisai reiškia šešerybėje, laipsnyne, aštuongubame kelyje ir kalbose.

- Žmogus turėtų gyventi kryptingai, tikėti, kad yra kelias ir jo ieškoti, remtis kelio pavidalu, vaisinga jo prielaida.

- Ko labiau sąmoningai išgyventi sąlygiškumą. Palyginti pirmines sandaras. Kūno poreikius sąlygose išgyvename nesąmoningai. Tiktai išėjus už savo sąlygų galime juos išgyventi sąmoningai. Protu sąmoningėjame sąlygose vienu matu, širdimi dviem matais, or valia trimis matais.

- Dorovė yra išgyvenimas - gyvenimas savimi.

- Dorovė skiriasi nuo elgesio, kaip gyvenimas nuo gyvybės. Gyvenimas yra gyvybės išgyvenimas?. O gyvybė yra nauda.

- Dorovė yra savęs pakeitimas nešališka, nesąlygiška vertybe.

- Dorove žmogus pakeičia save nešališku dėsniu, nes jisai pats yra pakeitęs Dievą tariamai paneigdamas savo dieviškumą. Tad dorove žmogus prisiima savo dieviškumo pareigą, atsisako savęs, savo atsiribojimo ir savo šališkumo, savanaudiškumo.

- Dorovė yra doros bendrystės kūrimas

- Dievas kuria save (viską, pasaulį, mūsų sąlygas) ir atitinkamai bendrystę, žmogus kuria save (savo sąlygas) ir atitinkamai bendrystę. Ar tai ta pati bendrystė?

- Savo elgesį grindžiame nuostatomis - dėsniais - kuriais galime pasitikrinti ir kuriuos galime patikrinti.

- Čia svarbu, kad savo nuostatomis galime pakeisti save - užtat galime tikrinti tiek save, tiek juos - tiek pasąmonę, tiek sąmonę. Gyvendami sąmone savo pasąmonę išsakome nuostatomis, dėsniais, vertybėmis, kuriuos galime tikslinti ir tobulinti. Šis sąmoningumas yra mūsų laisvės šaltinis, nes leidžia gyventi tiek pasąmone (žinojimo pagrindu - įkūnyta vertybe), tiek sąmone (nežinojimo pagrindu - iš nežinojimo išpuoselėta, sutverta vertybe).

- Tiesa mus išlaisvina nes ja išeiname už savęs - nebandome apsisaugoti, kas bus - nesidangstome savastimi. Savastis turėtų leisti mums labiau prieiti, labiau išeiti už savęs.

Susigaudome, renkamės platesnę apimtį, sąmoningėjame

- Dorovė yra susigaudymas, susivokimas (jog nesuvokiame)

- Dorovė yra Sūnaus susivokimas.

- Dorovė yra susigaudymas, jog mūsų sąlygos susidaro iš žinojimo, tačiau už mūsų sąlygų yra besąlygiškas nežinojimas. Pavyzdžiui, mūsų protas gyvena žinojimu, už kurio yra tiktai nežinojimas. Ir netgi mūsų kūnas gyvena veikla, už kurios yra neveikla. Ir panašiai su širdimi ir valia, su visais klodais. Tad tai yra atpažinimas Dievo troškimų: savarankiškumo, užtikrintumo, ramumo, meilės.

- Dorovė išsako žmogaus būklę. Žmogus gyvena trejybės ratu. Jisai skiriasi nuo Dievo sūnaus tuo, kad jis dar nesusivokia, jog yra Dievas. Užtat jisai nepaklūsta Dievui, nenuolankus jam, nesupranta savo santykio su juo, nemoka Dievą įpareigoti, melsti.

- Dorovė yra raktas į mano klausimus dėl sandarų.

- Dorovė yra koks elgesys "turėtų" būti.

- Sąvoka "turėtų" skiria elgesį ir dorovę.

- "Turėtų" reiškia "Atsakyti už". Sąvokos "turėtų" atsakomybės apimtis. Palyginti "būtinas, tikras, galimas" (iš šalies) ir "esu, veikiu, mąstau" (išgyvenama asmeniškai).

- Apibrėžimas "turėtų" yra pagrindinis turinys. Padalinimai, atvaizdai, aplinkybės ir visos trys kalbos (lūkesčių rūpesčiais, abejonių reikšmėmis, poreikių įvykiais) išsako, ką reiškia "turėtų". Pavyzdžiui, padalinimai išdėsto mąstymo galimybes; abejonės - patinka, reikia, tikra, keblu, protinga, neteisinga - visos susijusios su privalėjimu; troškimai ir lūkesčiai susiję su tai, ko tikimės.

- "Turėtų" suprastina sąlygiškai ir, taip pat, besąlygiškai.

- "Turėtų", tai nepriklausymas nuo sąlygų, užtat tai besąlygiškumo išraiška. Tačiau pačios sąlygos gali būti besąlygiškos, ar besąlygiškumas gali būti sąlygiškas, užtat tada šį sąvoka painiau taikoma.

- Derėjimas. Susigaudymas, jog galima įvairiai suprasti, ir kaip derėtų.

- Elgesys išsako, kaip renkasi. (Atsakymas) Užtat, kaip galėtų rinktis? (Klausimas) Ir iš to, kaip galėtų, būtent kaip turėtų rinktis? (Turint žinių.) Vardan to, kuris neabejingas, kuriam rūpi? (Esant pastoviai, išliekamai savasčiai.)

- Dorovė yra ištisinis savęs tikrinimas.

- Dorovės raktas gali būti pačios dorovės pavidalas: dorovinis mąstymas mus išjudina spręsti ar save išsijudinti.

- Dorovė yra mūsų dalinė, sąlyginė atsakomybė, tame tarpe tarp nežinojimo ir mūsų vertybės.

- Dorovė yra dalinis valdymas - santykyje su Dievu - kuria vykdome Dievo valią, paklusdami, tikėdami ar rūpindamiesi, taip sukdamiesi trejybės ratu. Dalinis valdymas iškyla Jėzaus palyginimų pamokymuose.

- Dorovė iškyla tarpe tarp vertybės ir Dievo, tarp visuminio žinojimo (suvedimo) ir nežinojimo (nesuvedimo), meilės vardų (vertybių) ir jos neįvardijamumo, tai yra tarpe, kuriame iškyla klausimai. Klausimai sudaro klausimų ratą apie vertybę. Gal kiekviename padalinimui po vieną klausimą, jie išsako tarpus tarp vertybės ir tos Dievo begalinės meilės už šio pasaulio.

- Dorovė: gyvenimas mažais žingsneliais (dangaus karalystė) - 7tas požiūris - nerimas (jauduliai) - ar darau ką nors tuo klausimu (dvejonės) - rūpintis kitu

Ugdome sąmoningumą

- Dievas: Dorovė yra sąmoningumo išlaikymas

- Dorovė yra sugebėjimas pačiam klausti gyvenimo klausimus, užtat pačiam apibrėžti įmanomus atsakymus. Užtat klausimai: ką, kaip ir kodėl mes veikiame? ką, kaip ir kodėl mes turėtumėme veikti? yra būtent tie mūsų klausimai, kurie turbūt sutampa su vertybes tikslinančiais klausimais. Šie klausimai išsako mūsų vertybės nepakankamumą:

- Kaip mums taikyti savo vertybę? (ką, kaip, kodėl veikiame) Kaip apskritai (ką veikiame), kaip savo gyvenime (kaip veikiame) ir kaip plačiau (kodėl veikiame)?

- Kodėl mes netaikome savo vertybės? (ką, kaip, kodėl turėtumėme veikti) Kodėl jos nėra (ką turėtumėme veikti), kodėl ja negyvename (kaip turėtumėme veikti) ir kodėl jos nemąstome (kodėl turėtumėme veikti)?

- Dorovė yra sugebėjimas pačiam klausti gyvenimo klausimus, užtat pačiam apibrėžti įmanomus atsakymus. Užtat klausimai: ką, kaip ir kodėl mes veikiame? ką, kaip ir kodėl mes turėtumėme veikti? yra būtent tie mūsų klausimai, kurie turbūt sutampa su vertybes tikslinančiais klausimais. Šie klausimai išsako mūsų vertybės nepakankamumą:

Išreikalaujame Dievo būtinumą, sąmoningumo būtinumą

- Dievo būtinumo pagrindas

- Dievas "turėtų" iškilti net ten, kur jo nėra. Jisai "turėtų" būti būtinas. Tačiau, jisai nėra būtinas, kaip žinome iš dešimt Dievo įsakymų, jisai nebūtinas. Mat, Dvasiai žiūrint iš šalies, gali tiesiog būti tarpas, kuriuo tiesiog gyvename. Užtat, visgi, mumis Dievas yra būtinas.

- Žmogaus sąlygos yra tas tarpas, kuriame Dievas nebūtinas. Dievas yra pasitraukęs bet dar neiškilęs. Dievas visapusiškai laukia, trokšta, tad Dievas myli. Dievo meilė yra jo nebūtinumas, nes meilė yra Dievo esmė. Dievo meilėje esame mes.

- Dievo būtinumas tad sprendžiasi žmogaus elgesiu. Mes esame tas Dievas, kuris "turėtų" būti. Mes, būdami geri, gyvendami Dievu, išryškiname Dievą, koks jisai yra geras.

- Dorovė yra gyvenimas Dievu (ir savimi, ir visais - Dievo šokiu - arba išėjimu už sąlygų - šešerybe).

- Trejopa meile gyvename Dievu už mūsų, kuriuo mylime. Trejopomis sandaromis gyvename trejybės ratu, slenkame pirmyn ir ne atgal, renkamės teisingą požiūrį iš dviejų. Ryšį su Dievu už mūsų (išorinį požiūrį) įsisaviname ėjimu trejybės ratu (vidiniu požiūriu). Panašiai - teigiamas jausmas įsiamžina trejybės rato dorybe.

- Mes elgiamės, gyvename šiaip, o Dievo Sūnus gyvena taip, kaip turėtumėme gyventi. Jisai gyvena Dievu.

- Dorovė yra gyvenimas viena - gyvenimas visais.

- Mūsų troškimas yra gyventi viena. Tačiau mūsų būklė yra tarsi lyg tai mes nesame viena. Dorovės esmė yra, nepaisant nevienumo sąlygų, gyventi viena. Mūsų tokie lūkesčiai dažnai nepasiteisina, o mums tenka rinktis, ar laukti to ko trokštame, ar to kas bus? Juk sprendžiame, laukiame kiekvienas atskirai.

- Yra trys vienumo pagrindai: vienumas Dievo už mūsų; vienumas asmens gyvenančio visais; vienumas mūsų asmenybių įvairovės pilnatvės. Atitinkamai paklūstame, tikime ar rūpinamės.

- Mūsų vienumo pagrindas negali būti mūsų pačių pasirinkimas, mūsų pačių lūkestis ir sulaukimas, bet už mūsų valios glūdinti Dievo valia. Tad mūsų valia turi atsiduoti Dievo valiai, kaip mūsų vienumo būtinam pagrindui.

- Ian mintis: Meilė neapibrėžtina, jos nevaržyti, kiekvieno žmogaus meilės samprata skirtinga, tačiau tikslas yra meilę suvesti, jog mūsų meilė yra ta pati meilė. Šis uždavinys iškyla ir kategorijų teorijoje. Nežinojimo - nežinomojo apibrėžimas yra panašus iššūkis į nesančiojo (skylių) apibrėžimą, tad į homologijos iššūkį.

- Dorovė: turime rūpintis visų labu, ne savo labu. Platono žodžiais, rūpi visos valstybės gerovė, ne kurios nors jos dalies. Užtat rūpi ne teisingumas paskiriems žmonėms, bet visumai. Užtat turime gyventi, aukotis visų labui. Tada kitaip atrodo teisingumas.

Kaip paaiškinti, jog Dievas nebūtinai geras:

- Jisai yra visoks, tiek geras, tiek blogas.

- Žodis "geras" jo nevaržo.

- Mūsų gerumo supratimas labai ribotas.

- Žmonės pažeisti ir pažeidžiami ir neaišku, ar Dievas neabejingas.

- Jis nebūtinai geras, bet gal visgi geras. Panašiai, jis nebūtinai blogas.

- Tvirtinti, jog Dievas yra geras, tai yra gyventi uždaroje santvarkoje, kurioje jau viskas išspręsta, kur entropija didėja ir viskas yra, kur gyvenimas būtinai teisingas, kurioje Dievas jau iš anksto viską žino ir yra sutvarkęs ir išmąstęs. O tvirtinti, jog Dievas nebūtinai geras, tai gyventi malonės aplinkoje, kur jo gerumas yra jo dorybė.

- Jeigu norime bręsti, turime nesitenkinti esamu gyvenimu.

- Dievas gyvendamas mumis atsiliepia mumis.

- Gerumas yra tiktai šioje santvarkoje, o Dievas yra už santvarkos

- Požiūris, kad Dievas geras, o žmonės nusidėjėliai yra bjaurus, nes žmonės visuotinai yra pažeisti, tad nevisai pakaltinami. Ar Dievas abejingas tokiai padėčiai? Manytina, kad jis negali būti (tada jisai nėra geras), o jeigu jisai dalyvauja (kaip manytina), tada jo dalyvavimo pasekmės yra labai neaiškios (ir nebūtinai geros - dažnai tiesiog neaišku). Pasimokiau iš pažeidžiamumo, kurį išgyvenau per Dainą Nemeikštienę ir John Kay.

Dorovė - mes renkamės apibrėžti save, su kuo tapatinamės - kas mes esame?

Kodėl yra dorovė?

Dorovė yra amžinos brandos pagrindas, nes jinai leidžia mums sutapti su savimi, tai kaip elgiamės ir tai kaip turėtumėme elgtis.

Kaip yra dorovė?

Dorovė mus sulygina su mūsų aplinkybėmis, užtat tuomi mus apibendrina ir mus išreiškia įsakymu mylėti.

Kodėl derėtų veikti?

Kertinė vertybė

- Kertinė vertybė yra žmogaus atsakymas, kodėl jisai turėtų veikti.

- Kiekvienas žmogus susiranda sau būdingą, asmenišką kertinę vertybę, visas kitas aprėpiančią.

- Visi žmonės vertina visas vertybes ir jos visos susijusios.

- Kertinė vertybė žinojimu išsako tai, ko nežinome. Užtat jinai yra mūsų teisingiausias žinojimas tačiau visada netobulai išsakyta. Tad galime amžinai gyventi ir ją amžinai ryškinti.

Vertybės ir klausimai

- Dievas klausia ar jisai yra (būtinas)? Žmogus klausia, kas aš esu? tai Ievos klausimas, kertinės vertybės, kuria jinai yra ne tik atsakymas, bet ir klausimas, amžinas gyvenimas, nes vis ryškėja. Tai visų klausimų pagrindas.

- Kertinė vertybė (visuminis žinojimas) mums atstoja troškimą (nežinojimą), o vertybę išplečia lūkesčiai, lūkesčius išplečia abejonės (ypač apie nerimą), abejones išplečia poreikiai (ar tikrai esame viena). Vertybės, lūkesčiai, abejonės, poreikiai yra troškimų ženklai. Užtat šių lygmenų poros yra ženklų savybės.

- Vertybės, Tėve mūsų: Kai turi ryšį su Dievu, tai kelio žinojimas. O kai neturi ryšio, tai kelio nežinojimas, tai nors nekelio žinojimas.

- prasmė tai klausimas kuris suveda, būtis tai atsakymas kuris isveda

Kaip derėtų veikti?

Elgesį reikėtų pakeisti dorove

- Elgesį (kaip gyvename) derėtų pakeisti dorove (kaip turėtumėme gyventi).

Gerumo kryptys: Vertybės klausimai

- Kertinę vertybę supa klausimai vis naujai išryškinantys, kaip mums žinoma vertybė neprilygsta jos išreikštam nežinojimui. Gerumas yra tasai laisvumas, tas neatitikimas, ir gėrio kryptys nurodo klausimų galimybes.

- Gerumas iškyla gėrio kryptimis, jisai labai įvairus. Tačiau gerumo pradas yra gera širdis.

- Reikia žiūrėti ne į gerą širdį (Dievą), bet iš geros širdies į gerą valią, gerą naujieną.

- Gerumas yra laisvumo šaltinis, jo dvasia.

- Geras pradas - gera širdis. Mumyse yra geras pradas, kuris išryškėja vertybe. Ir myliu Ievą nes ja mylėdamas galiu pajungti tai vertybei tiek savo kūną, tiek protą, tiek širdį. O permainos išsako tiek atitrūkimus atitokėjimus tiek saitus tarp šių savasčių netroškimų. Dievo Tėvo pirmapradiškumas savarankiškume, nieko troškime, o jam išeinant už savęs, dieviškumas iškyla vertybėse, visko netroškime, Sūnuje.

Ką derėtų veikti?

Elgesį reikėtų išplėsti dorove

- Elgesį reikėtų išplėsti dorovės sąvokomis kaip nežinojimu, meile, Dievo valia, Dievo įsakymais) išplečia elgesį.

- Derėtų vis išplėsti sąvoką "derėtų".

Vienumas

- Mums kaip asmenybėms reikia išsiskirti, o mes bandome jų pagrindu vienytis, ir priešingai, mums reikia gyventi bendru asmeniu.

- Asmenų vienumas: Tiesa yra tai, kas leidžia visoms galimybėms atsiversti, paaiškėti, pasireikšti, jų nevaržo.

- Nenuoseklumą, pavyzdžiui, Šventajame rašte, kaip elgėsi su Marija ir Zachariju, įžvelgia tas, kuris ieško bendro dėsnio, užtat neranda. Jo neranda tas, kuris nori pateisinti paskirą atvejį.

Ar derėtų veikti?

Elgesį reikėtų sutapatinti su dorove

- Žmogus jau veikia.

Dorovės užrašai

- Gerumas ir dorumas. Dorumas yra gerumas bendram žmogui, tad visiems. O šiaip gerumas gali būti sau, paskiram žmogui. Tad skirtumas yra dviprasmiškas. Dorumas palaiko bendrą gerumą, užtat palaiko vienumą. Tai didėjantis laisvumas. Tuo tarpu gerumas gali reikštis ir mažėjančiu laisvumu.

- Nenoriu šiaip sau mylėti, ar šiaip sau gyventi, bet noriu gyventi bendru žmogumi. Kaip suderinti? Kaip skiriasi "šiaip žmonės" nuo bendro žmogaus?

Moral law is law which one imposes on one's self.

Trys dorovės klausimai pagrįsti susiskaldymu (dviprasmybe). Kaip mums prisiversti? Atskyrimas sąmonės ir pasąmonės. Tai pagrindas septynerybės gėrio ir blogio atskyrimo.

Kalba esam atviri kitam.

Dorovinis mąstymas yra žiūrėjimas pirmyn (kaip galėtumėme elgtis) ir atgal (kaip elgiamės). O tai vyksta dabartyje - abi kryptis deriname. Užtat laikas ir erdvė (penkerybė) yra pagrindas dorovei (šešerybei).

Šešerybė įpina dorovę į mūsų veiklas ir veiksmus, į mūsų trejybės ratą.

- Technologija - standartai - mus skiria

- Menas - išimtys - mus jungia

- Dorovė - galimybė rūpintis išimtimis. O kaip su dorovės bendrais dėsniais? Asmuo ir asmenybė? Mylėk artimą kaip save patį?

Ar veikiame - veikiame ir dera mums veikti.

Dorovėje žalingai klaidina dirbtinas atsisiejimas (kitų reikalų nagrinėjimas) ir dirbtinas įsivėlimas (sąlygų priėmimas, tarsi jos būtinos).

Dorovės atsakymas: Jau veikiame, atsakymo į klausimą: Ar derėtų? O logikos klausimas: Ar galėtų? Užtat etika ir logika yra priešingybės, bene remiasi skirtingais ketverybės atvaizdais: etika pažinovo, o logika pažintojo.

Derėjimas yra idealistinis - jeigu nusakysime kodėl, kaip ir kas dera, tai būtinai tą padarysime. Tai kaip suderinti tai su ketverybe?

"might makes right" - Dievo galia, mūsų galios ribos, apibrėžia mūsų teises ir įsipareigojimus.

Laisvė

- Laisvė, kaip siekis, yra laisvė nuo savęs.

- Laisvas nuo jausmų.

Dorovė ir elgesys

- Elgesys ir dorovė yra tarsi du susiję atvaizdai, tačiau kodėl abu išreikšti pažinovo klausimais: Koks? Kaip? Kodėl?

Kas mes esame

- Dorovė: nesame savo introspekcija (awareness), esame jos rėmai. Tapatintis su savo introspekcija (su savo žibintu) yra dorovinė klaida.

Poreikiai

- equality - need for self-esteem, - government can't pursue self-esteem and freedom at the same time. You can't change the rules of the game in both ways with the same priority, or can you? Over focus on freedom can keep us from moving on to self-fulfillment and degenerate back into equality.

Dorovės ratu išskiriame (amžinu gyvenimu) derėjimo klausimą į buvimo ir galėjimo klausimus, tada naujai suvedame (sąlygose - gyvenimu) nauju klausimu.

Dorovė: suskaldymas į du takus - patikrinti esamą sprendimą ir ieškoti kito sprendimo - tai požiūrių skaldymas vedantis į septynerybę. O galime persimesti iš vieno tako į kitą ir "geras" yra tas kuris sulaukia patvirtinimo. O jeigu nesibaigia?

Yra trys doroviniai klausimai (ką derėtų veikti, kaip ir kodėl) ir daugybė dorovės sąvokų sieja šiuos klausimus, mus veda iš vieno į kitą.

Bandom šią esmę išsakyti turi klausimas, kad galėtumėme būti už savęs, atsisakyti savęs.

Tėtė: reikia pateisinti gyvenimą, nusiteikti kažką kiekvieną dieną padaryti kas būtų bendrai gera.

Žmogus likimo verčiamas link didesnio jautrumo. (Sąžinės) (Meilė sau) Ir į tai įeina pasirinkimas kam mes norime būti jautrūs (mylėti kitus). Tad išsiskiria šios dvi galimybės ir kiekvienas savaip nusistatome, kaip rinktis tarp jų. Ir tas nusistatymas yra mūsų būdas, kurio nežinome. Ir tą nežinojimą mums išreiškia mūsų kertinė vertybė. Tad tas nežinojimas (ta tiesa) yra mūsų laisvės pagrindas. Tiesa yra, kad mes nežinome. (O tai prieštaravimas.) Ryšys su Dievu ryškina tą laisvę.

Tautvydo bevardė galybė - tiesiog šėtonas.

Elgtis kaip matau, kad kiti elgiasi.

Valdyk padėtį ir įtakok.

Nesielk kaip jie elgiasi.

Dėl vienos avelės paliko visą kaimenę = šaukštui gėriui priims kalną blogio.

Savęs suvokimas

Žr. Susikalbėjimas, Atjautos, Ir trys, Laisvumas, Šešerybė See also: Factoring, EverythingVAnything

Kadaise tyriau keturis suvokimo lygmenis: 0) suvokimą, 1) savęs suvokimą, 2) bendrą suvokimą ir 3) susikalbėjimą. (Anglų kalba: Understanding, Self understanding, Shared understanding, Good understanding.) Įdomu ar bendras suvokimas sutampa su Tomasello tiriamą "joint intentionality".

Bendras suvokimas

Bendras suvokimas yra žmogaus požiūris į Dievo požiūrį į žmogaus požiūrį į Dievo požiūrį.

We apply shared understanding when we LoveOurNeighborsAsOurselves.

The Sevensome is the Structure for shared understanding. Shared understanding expresses the SecondaryStructures on their own terms, as self-standing, and relating humans as equals.

Shared understanding is an Operation +3 because it takes us from the Nullsome to the Threesome. [AddThree +3] adds Slack - three perspectives - yielding Interplay and SharedUnderstanding.

[AddThree +3] SharedUnderstanding allows for a PersonInGeneral by understanding Representations. SharedUnderstanding makes it possible for a perspective to be taken up by an Other, which it introduces. This makes it possible for God and heart to take up each other's perspectives. Perhaps Human is that Other.

See also {{Factors}}, SecondaryStructures, SharedUnderstanding, {{Equations}}, {{Structure}}, {{Activity}}.

AndriusKulikauskas: Factoring is a structural idea for which I am seeking an intuitive interpretation. I have observed six SecondaryStructures which I think are related to factors of the number 24 = 2 x 3 x 4, as there are 8 = 2 x 4 {{Divisions}}, 6 = 3 x 2 {{Representations}}, 12 = 4 x 3 {{Topologies}}, and also three {{Languages}} which may be understood as shifts relating these three kinds of structure.

I have observed that this approach to defining the secondary structures is apparently related to SharedUnderstanding, as there is another approach to defining them, in terms of God's injecting himself into primary structures, which is related to GoodUnderstanding.

Also, it is possible to derive these factors as arising from the {{Operations}} [AddOne +1], [AddTwo +2] and [AddThree +3] acting on the {{Onesome}} (which may be thought of as pure structure) and yielding this onesome back as one perspective within the {{Twosome}}, {{Threesome}} or {{Foursome}}, respectively.

Factoring also opens up the way for a SeventhPerspective: ZeroStructure (all factors separate), and then an EighthPerspective: ZeroActivity (all factors together).

Intuitive interpretation of the {{Factors}}

I am trying to understand what might be the significance of these factors.

It seems that the 2 factor is from having unequals manifest as equals (as in BeginningVEnd), and the 4 factor is from having equals manifest as unequals (as in SpiritVStructure). How to understand the 3 factor?

If we have an unequal relationship, such as A to B then we can still emphasize one or the other role (A or B) and they become equals.

If we have a relationship of equals, such as X and Y, then we can consider them as unequals by introducing a relationship "to", generating: X to X, X to Y, Y to X, Y to Y and pairing X to X with X to Y (keeping the first element fixed) and pairing Y to X and Y to Y (also keeping the first element fixed). This is nonsense. Hmmm.

I ask God, and my understanding from that is: the factors are those structures which coincide with their activity. Humans go beyond themselves through the wholeness of structure, and humans immerse themselves in structure by way of activity.

I suppose this is because the factors are those structures that result from acting on the onesome, which as a DummyVariable reflects and expresses the action upon it. The activity is given by the operation.

In my own observations, the factors seem to express the relationship between {{Structure}} and {{Spirit}}. We may think of the {{Onesome}} as pure structure. The factors result from the operations acting on this pure structure and placing it within a framework (a factor). This framework allows us to consider that pure structure in more than one way (specifically, in two, three or four ways).

- The two-factor allows us to consider the primacy of structure and spirit (or the {{Beginning}} of structure and spirit). We may have structure manifest spirit, as when spirit is thus is. Or we may have structure yield spirit, as when spirit is not, even so, is. In the first case, spirit is prior to structure, and in the second case, structure is prior to spirit. If we allow for this (and only this) to be ambiguous, then we have {{Topologies}}.

- The three-factor allows us to consider the convergence of structure and spirit (or the {{End}} of structure and spirit). We may have spirit understand structure, so that the end is spirit. Or we may have spirit come to understand structure, so that the end is their relationship. Or we may structure be understood by spirit, so that the end is structure. If we allow for this (and only this) three-fold ambiguity, then we have {{Divisions}}.

- The four-factor allows us to consider the separation of structure and spirit (or the relationship of structure and spirit). This may be {{Everything}}, {{Anything}}, {{Something}} or {{Nothing}}. If this (and only this) is left ambiguous, then we have {{Representations}}.

In each case, we may think of the factor (and any of its perspectives) as allowing us to understand the wholeness of a structure. This is what is significant about the twosome, threesome, foursome: they may be considered as resulting from actions on the onesome.

We may then consider the structures as arising from fixing two aspects of the relationship of spirit and structure (or {{God}} and {{human}}, respectively), and leaving another aspect ambiguous. We may think of the beginning as the spiritual whole, and the end as the structural whole. This yields:

- {{Divisions}} fix the spiritual whole and the relationship, but leave the structural whole ambiguous. (Thus a division has several perspectives, and it is not clear if the weight is in the part or the whole).

- {{Representations}} fix the spiritual whole and the structural whole, but leave the relationship ambiguous. (Thus the distance between the two is left unclear).

- {{Topologies}} fix the relationship and the structural whole, but leave the spiritual whole ambiguous. (Thus a topology leaves unclear if it is experienced as such, or coming from beyond it).

===Binary Operations===

I have thought that the 2 x 4 = 8 divisions, 3 x 2 = 6 representations and 4 x 3 = 12 topologies are given as products. But it might actually be more interesting than that. It might be better to think of them as applying three different kinds of binary operations:

- The 12 {{Topologies}} are indeed a product of the {{Foursome}} and the {{Threesome}}.

- But the 6 {{Representations}} are the union of the {{Twosome}} and the {{Foursome}}.

- And the 8 {{Divisions}} are the intertwining of the {{Threesome}} and the {{Twosome}}, yielding two additional perspectives, so that we have 8 = 1 + 3 + 3 + 1.

This very much accords with what I've observed. I'm wondering what the structural implications are elsewhere. I suppose it doesn't affect the position of the three languages within the eightfold way because that is given by the shifts in the structures themselves, not their components.

Note also that these structures may still be derived by the {{Omniscope}} as products 2 x 3 x 4, and yet arise fresh when they are reinterpreted, perhaps by human eyes, so that the divisions and the representations switch places.

===More notes===

These are perhaps fundamental to shared understanding. They may be the entities that are factored 2 x 3 x 4. The factoring may have us think of them in pieces. Each piece is a mapping from the onesome (as a whole) to the onesome (as a perspective). Perhaps the ambiguities are as follows:

- We have a twofold ambiguity (and topologies) if we presume there is a direction, but we don't know which it is, either forwards or backwards, from which we are interpreting the operation (either from the initial division (beginning) reaching out, or from the final division (end) going back to the roots). This ambiguity is given by the equation 1+1=2. This is the outlook of the end, looking backwards in terms of two representations of the division to which it is returning, namely, beginning and end. This is the ambiguity between God and human when it is not clear who is the originator for a shift in perspective - God or human?

- We have a threefold ambiguity (and divisions) if we presume there is an operation, a relationship between beginning and end, but we don't know what it is, either +1, +2 or +3. This ambiguity is given by the equation 1+2=3?. This is the outlook of the relationship between beginning and end.

- We have a fourfold ambiguity (and representations) if we presume that each division has its own state, but we don't know what it is, yielding: (beginning or end) to (beginning or end). These are four levels of understanding. This ambiguity is given by the equation 1+3=4?. This is the outlook of the beginning, looking forwards in terms of four representations of the division which it is reaching out from, constructively presuming that relationship.

I think that these presumptions are the constructive hypotheses. The factoring then makes sense as a split of determiniteness and ambiguity as part of such a presumption and the engagement of an other. I should also think of them in terms of the heart? and the inversion effect.

Apparently, we should attribute the forwards direction when operations act on divisions with four representations: nullsome, onesome, twosome, threesome. And we should attribute the backwards direction when operations act on divisions with two representations: foursome, fivesome, sixsome, sevensome. And these presumably also list out the levels of understanding. But I should look into this when I know more.

The factoring assigns factors to either a human view (one-track, deterministic, where a perspective is chosen) or to God's view (all-track, nondeterministic, where all perspectives are taken). These views are the generation of what is relevant for an absolute perspective: the onesome, twosome, threesome - considered as operations that also generate whate is relevant for a relative perspective: the foursome, fivesome, sixsome - acting on either the nullsome or the threesome. This is made a shared perspective by considering its action on a whole - on the onesome - and allowing for mixed modes. So factoring is a categorization of views understood as operations on wholeness.

Question: How does the Other arise in factoring as the seventh perspective? How does the Other express that total ambiguity which is partially evident in structures and more evident in activity? How is that ambiguity expressed as a function (+1, +2, +3) from wholeness to wholeness? And how is nonambiguity, determination likewise expressed by that function? In what sense are we thereby opening ourselves up for view by somebody else? And how does that mediate our absolute and relative perspectives?

Shared understanding is based on the fact that it is the same good in both God and human. In Representations, that good is Waiting and it is separate for God and human. In Topologies, that good is Believing and it is together in God and Human. Either way, there is SharedUnderstanding. See: EverythingWishesForAnything. Note that here the slack of the Wholeness is in the case of Representations.

Recall the destructionism of the threesome onto the threesome which yields people, words, qualities - these may be considered as anythings on which the threesome of structure and threesome of activity may share perspective from, their shared point of reference, their stand.

I think the Other arises as the one who experiences the taking a stand, following through and reflecting of the Absolute perspective - and makes it continuous - and also is the center for the Relative perspective - with regard to which there is self-correction in taking a stand, following through, and reflecting. It is a person-in-general that bridges the Relative and Absolute perspectives through recurring activity. It is what allows us to take up another point of view rather than just our own - to take up another's needs rather than just our own, for example.

This Other is perhaps that Stand - the Anything - which arises in both the Relative and the Absolute perspectives - it is the continuity of this Stand. It is the root of a person and allows us to communicate with them. The Other is what steps into the Absolute perspective and steps out of the Relative perspective. Perhaps this is why it is bounded, it goes counter to the natural direction where Absolute is God's point of view, framing, and Relative is human's point of view, immersed. Slack is what allows the Other to be in each case, and for it to be the same Other in both cases. How does that relate to the sixsome and factoring?

We think of that self-standing whole (the Other) as a recurring activity within a threesome that is held together by shifts +1, +2, +3. If these shifts are all considered activity, then we have recurring activity and the Other. But some of these shifts may be taken as structure, which means that they set a definite path from whole to whole, with no ambiguity. If one is fixed, then we understand a shift as taking us from one activity to another activity as part of our self-correction (as an Other) with regard to some third structural center that is fixed. If two are fixed, then we understand them as where we are coming from and going to, and there is an undefined action that the Other experiences along with us from one to the other. Why is there a circle of shiftss +1, +2, +3? I need to look at the details of each type of structure that is generated.

This is the level that distinguishes Choosing and GoodWill.

Shared understanding is the arisal of an Other (perhaps the understanding of this other, or the separating out of this other) as a SeventhPerspective that relates the Heart and God - the Releative and Absolute perspectives. This is the seventh perspective which the relative perspective circles around (and therefore posits). It is also the recurring activity of the absolute perspective that it walks through. And so these two approaches which it combines are like immersing oneself into a perspective (stepping in) and framing a perspective (stepping out). In this way, through the other, we can induce fluttering by both stepping in and stepping out. The spirit can thereby flutter amongst us as we make possible a person-in-general, almost as single frames can form a movie, a moving picture. A person is that into which they immerse themselves, which is ever deeper love. Whereas God is that into which they step out, which is ever distant frames. In the sequence: God - heart - other - God (as in loving them), we have that humans conflate the first and the last, thus yielding a three-cycle. But God keeps them separate. In conflating them, God and human can coincide. God in all ways supports that Other which can relate him to the heart. Among those others is the heart, so may they coincide? If the heart and the other coincide (by the heart going beyond itself), then God(0) and God(3) coincide (perhaps by internalization). I'm looking for the rationale by which the relative three-cycle may entertain a seventh perspective (perhaps which it considers absolute) and the absolute three-cycle may entertain it as well (perhaps as that which it considers relative). So that they are able to share a perspective, by engaging the complement. And how does this relate to slack, increasing and decreasing? And how does this relate to factoring and the factors and the secondary structures? And then later it will become a question of whether to consider oneself subordinate or superordinate. Also, the idea of understanding as applying to a hole which is first empty (the truth) and then the Self and then the Other and finally God - and in each case adding to this hole three or however many perspectives so as to create the relevant framework.

Self-understanding separated activity from structure. Shared understanding switches their primacy and has us start with the self-correction of the threesome for activity. Here we are faced with choices between good and bad, better and worse, the best and the rest. Shared understanding separates these and considers good as that which preserves wholeness, and so this gives rise to a seventh perspective which is the preservation of wholeness, and we take as Other. Given wholeness, the preservation is considered as an operation +1 (for the good), +2 (for the better) or +3 (for the best). The threesome of structure is understood as a projection of the threesome of activity onto what preserves the wholeness. In this sense, structure is always good. But the perspectives of the threesome of activity allow good and bad to travel side by side. Through the good we have shared understanding. This also allows us to define slack and good by way of the seventh perspective. Good is what allows us to relate an absolute perspective and a relative perspective. Good arises by mapping back from the threesome of activity into the threesome of structure. So the threesome of structure is not aware of this concept, of its goodness, except by way of this map. So the Other is always good. This is a separation of what is particular (and does not preserve the good) and what is general (and does preserve the good). Note that this seventh perspective is understood to be the recurring activity within the threesome of structure. This recurring activity allows us to understand that there might be bad alongside good within structure, but only contingently, as relevant for preserving the whole. The factoring allows this to take place for individual perspectives. Also, we get Factoring because each operation may be considered as undetermined (and not necessarily preserving the good) or as determined (and preserving the good). So the determined factors are considered structure, and the undetermined factors are considered activity. For the seventh perspective, I imagine that all factors are pure structure, there is a complete focus on the good, a perfect person, a total structure. Then the eighth perspective is a total activity by which God goes beyond himself and is able to come out into our world. The factors are maps that are into and onto wholeness, hence wholeness preserving. They yield structure, which is purely good, hence this lets us have a self-standing opposite. They open windows by which other perspectives can look inside of us. A representation is perhaps a view from any one of the perspectives of the sixsome through the Other and onto a selection of the perspectives. The Other then plays a role much like that of the whole yet independent.

Now it is important to try to define the secondary structures as arising from this kind of factoring. The factors should be related to the operations. For example, the operation +2 acting on the wholeness may be thought of as yielding wholeness="divided" and also "dividing" and "not-dividing" as three choices by which the wholeness may be preserved. These are left undetermined in the case of a division. The operation +1 acting on the wholeness may be thought of as yielding wholeness="absolute context" and also "arising context". These are left undetermined in the case of a topology. What might the operation +3 yield? that would be left undetermined in the case of a representation?''

Shared understanding is the Understanding that allows for a PersonInGeneral. It is the Understanding that focuses on that which we may presume to share with others. It involves three tracks acting in parallel: the general structure that is yielded by understanding, the activity that is given by self-understanding within that, and the slack that relates structure and activity when there is recurrence. This slack appears when we impose the sixsome onto the threesome given by these three tracks. We thereby allow for a person-in-general.

Shared understanding is the human view that good and God are the same. Good is that which human and God share. Yet God is more than that, but at this point human does not consider this. The human understands the SeventhPerspective to be Good and God and Life. Here the two concepts God and good are conflated by the equation life is the goodness of God. This equation is with regard to some Scope. If there is no scope, then the equation becomes Abslute, the concepts of God and good become separate, and we have GoodUnderstanding.

God is that which is separated from itself by "everything". The godlet (the heart which arises in the space that God opens up for it as he goes beyond himself) is separated from itself (it's self, it's structure) by "nothing" (it identifies with its structure that it has found itself in, awoken up within). Now, the "everything" (all contexts) and the "nothing" (no contexts) may seem (and the heart presumes initially) are symmetric, equal. Yet ultimately it becomes apparent that the heart distinguishes everywhere true and false (a "knowledge of good and evil") whereas for God all is true. Note here that "true / false" is a false "separation", a false "or", as it does not keep the two concepts separate, but rather combines them, blends them with an "either or".

As part of this growth in understanding, we may consider a "human" as that which "is" what it identifies with:

- A) first God's perspective, as separated from itself by everything, and then going beyond itself, a general "love" (and perhaps an empathy for the "world")

- B) then the heart's perspective, that which awakens within structure, and is separated from it's self (structure) by nothing, thus a "love of self" (so that the heart is like "personality" of a person-in-particular). Here we are one with ourselves.

- C) then the human (hopefully) identifies with an "other" by which God and heart coincide, thus one lives as a person-in-general, as "character" by which we are all the same (this is the key event in life, to live from this general perspective) This happens as the heart goes beyond itself (from a narrower scope to a broader scope - one of six ways - between nothing, something, anything, everything) as a loved one who is met by God receiving, loving, conceiving, supporting it. Here the human is an intermediary by which God outside and the heart within meet. Here we are one with others. This is about "love other".

- D) Finally the human identifies with the God who supports, loves the "other", is able to place that other within an understanding context by going beyond itself into the limitations of the other. This is to "love God". As the evangelist John says, we can't love God except as we love others.

AndriusKulikauskas: I'm trying to make what follows more understandable. It is a mechanics that relates various structures that I have observed. These are structural ideas that arise in trying to "make sense of the numbers", which is to say, make sense of the structures that I have observed.

Shared understanding is the acknowledgement of an [{{Other}} #] which is the same. It is the recognition of the ability to take up each other's perspectives. What is [{{Structure}} #] for one is [{{Activity}} #] for the other, and vice versa.

This is made possible by [{{Recurring}} activity], which is the driver for shared understanding.

In shared understanding, as we walk a third time around the [{{Threesome}} #], we have acting-in-parallel:

- +1 structure (God)

- +2 activity (heart)

- +3 a slack that mediates them (as activity evokes structure and structure channels activity). (God and heart go around together).

[{{Factoring}} #]

Factoring occurs because shared understanding is where [{{Structure}} #] and [{{Activity}} #] coincide. This is indeed how the sharing takes place - structure and activity coincide. This happens by way of the [{{Twosome}} #], [{{Threesome}} #], [{{Foursome}} #] because these are the divisions for which this is so. These are the structures which may be considered as products of the operations upon the [{{Onesome}} #].

Related reasons why factoring occurs:

- recurring activity allows the sixsome to be imposed. *shared understanding compares a level of understanding with a base level, thus yielding operations and factors.

Each operation can be understood to embed the previous ones. If we apply each of them to the [{{Onesome}} #] (the division of everything into one perspective - and the basis for "shared understanding" and for [{{Constructive}} hypotheses] that allow for that), then this can look like a chain of mappings from the whole (the onesome) to a new structure (twosome (1+1), threesome (1+2), foursome (1+3)) within which there is one perspective that may be attributed to the whole (any one may be selected - any one may have served as the original - this yields up to 2 x 3 x 4 possibilities - but also at any component, selection need not take place, need not be rendered explicit). Then the resulting structural totality can be factored by the sixsome (the total structure for layer 2) yielding the following (cyclically structured with regard to each other):

- 2 x 4 = 8 [{{Divisions}} #]

- 3 x 2 = 6 [{{Representations}} #]

- 4 x 3 = 12 [{{Topologies}} #]

- 3 = shift from 4 x 3 topologies to 3 x 2 representations: [{{Argumentation}} #]

- 4 = shift from 2 x 4 divisions to 4 x 3 topologies: [{{Verbalization}} #]

- 2 = shift from 3 x 2 representations to 2 x 4 divisions: [{{Narration}} #]

Here we may think of this as an interpretation of the motion through the three-cycle where each component may be [{{Structure}} #] (with one of its perspectives specified as corresponding to the whole) or as [{{Activity}} #] (where no perspective need be distinguished, and participation is understood to occur along all possibilities in parallel). The factoring pairs structure with activity in all possible ways, yielding [{{Independents}} #] and [{{Insignificants}} #].

Having understood this all as a "factoring" it is now possible to make sense of a seventh perspective which is pure activity with no structure arising at any component. This is the "slack" ([{{Zero}} structure], the possibility of no factors, and also that which can always slip between any two factors). In this way, we can go from the sixsome to the sevensome.

The human is [{{The}} end] and the other is [{{The}} beginning]. Beginning and end:

- may be distinguished (twosome) beginning: coexist as opposites; end: all are the same

- may be equated (threesome) end is beginning; not end?; not beginning?

- may take up each other as values (foursome) beginning to beginning; beginning to end; end to beginning; end to end (determine order)

This is how the threesome imagines God.

Here beginning and end are considered symmetrical. This possibility makes relevant recurrent activity as expressed by a general shift. Recurrent activity is that in which beginning and end are equivalent, there is circularity. The end takes up the perspective of the beginning, which it understands as 'an other'. '''

This is the level of the key question: should I look for God, or help God find me?

Note that the answer takes us further to go beyond ourselves to the eightsome in good understanding. We either allow ourselves to be found - or we hide ourselves, like Adam and Eve. Here it is a question of whether we allow ourselves to be found by an other who we take to be our equal. If we do, then we allow ourselves to be found by God as well. It is not a matter of whether we believe in God, but whether we allow ourselves to be found by God.

Recurrent activity is the origin of slack. We understand it as increasing slack and decreasing slack.

This general shift makes sense in two ways.How do we equate these two definitions?

- I look for God decreasing God's scope God and I are equal as in shared understanding. One is as a structural definition of shift through the structural products (this is a God's view of human's view, it is a global perspective). Here perhaps God's shift (into the threesome) is equated with one, two and three shifts around the human threesome - this makes for structures of size 2, 3 and 4. They are then multiplied together and partitioned. These perhaps represent structure, activity and slack.

- I help God find me increasing God's scope God is greater than I - as parent and child - as in good understanding. The other is as a movement between two scopes (this is a human's view of God's view, it is a local perspective). Here the human shift is reinterpreted as a move between two scopes defined with respect to God. This perhaps expresses activity going beyond itself into structure: activity evokes structure, and that structure channels activity.

Here God goes beyond himself through the shifts of the threesome. These shifts are the origin of slack (hence the sevensome). The shift in general is the seventh perspective, it is the general shift that is the equivalence of the three shifts of the cyclic threesome. It is the essence of goodness, slack. This is the quality of God. God acts through his qualities.

Secondary structure is a structural partition, and as such a shift or a shift of shifts

God and human are treated as the same. Here the structures are defined passively, structurally.

The threesome is important here as the human condition - that which is taken to be the same as the other.

The shift and the recurring activity are in the fact that the beginning and the end are interchangeable.

In the choices, there are six combinations. They are built from:

- 2 outlooks: God and human (going beyond oneself or cyclic shift)

- 3 equivalent perspectives in the cyclic threesome (shifts) - understanding, self-understanding, shared understanding (the beginning and end are conflated)

- 4 perspectives (going beyond oneself - where the beginning and end are kept distinct)

The point of a general shift - and of each shift - is that first one determination is made, and then another. The shift expresses a shift in determination (or perhaps likewise in ambiguation, where we have the reverse, a shift between shifts).

A shift is the gap between determinations. The shift is the fact that the secondary structure can be factored - broken down into factors that are bound by the shift.

Note that the 24 may be understood as [{{Equations}} #], and the factoring provides different ways of understanding those equations, how to relate the parts of the equations.

Big question: Why 2 x 3 x 4 ? and Why does it factor? One possible answer - that there is an additional unifying perspective included (such as nothing) that may represent our point of view (or God's point of view, or perhaps the shared point of view).

Answer: factoring occurs because slack is inherent in the distinction between structure and activity. Activity evokes structure, structure channels activity, and there is slack in (the redundancy of) this relationship. Activity expresses the participant, and structure is the complement for that, the self for that participant. (Perhaps activity is representation - the point of view of a participant within and upon structure.) Activity expresses the participant by being ambiguous. There should also be factoring into one part of 3 and three of 1. But these imply that slack is more than just activity/structure. One of these is the seventh perspective, the other is the eighth perspective. The whole point of the secondary structures is to make relevant this seventh perspective. Note that the twosome, threesome, foursome serve as building blocks based on the participant - their consciousness +3 of the lacksome, nullsome, onesome. The seventh perspective has something to do with recurring activity, with general shift.

Note: the components are the twosome, threesome, foursome because these are the components for which structure coincides with activity (hence there is no slack in their distinction). What do they have in common, what does this mean? It seems that they may be considered as the consequences of the operations +1, +2, +3 on the onesome. Here the onesome is a "dummy variable" which represents "pure structure" and as such reflects the activities +1, +2, +3 in their outcomes (twosome, threesome, foursome). Within each of these outcomes it becomes relevant to identify which of the perspectives is the original "pure structure". Hence we get a multiplicative choice: 2 x 3 x 4.

What seems to be happening here is that each of the operations +1, +2, +3 can be understood as both activity and structure. As structure, the operation may be projected as a transformation from the whole (as the onesome, a dummy variable) and into a part (corresponding to the onesome). The operations +3 (recurring activity), +2 (shift in perspective), +1 (going beyond oneself) are happening at the same time, and in that sense form a threesome of endless activity - a cyclic threesome +3, +2, +1. This, when acting on the onesome, looks structurally like 4 x 3 x 2 with choices being made (or not made). Where a choice is made, we have structure (and activity), otherwise we have simply activity. By taking the "onesome" as the basis for shared communication (for the constructive hypotheses)(and for the identification of structure and activity) we can express the sixsome upon this cycle 4 x 3 x 2 with three static structural families (specify two structures) and three dynamic structural families (specify one structure). In every case activity is what flows through all of the structural cycle - it is simply specified (and unspecified) at certain points as it passes through that cycle. This factoring (which results from the sixsome rethought in terms of the shared "onesome") opens up a seventh possibility - which is all structure specified: 4 and 3 and 2. Here we have both structure and activity, but not for one perspective or the other perspective, but for the shared perspective, all spelled out. This has slack because again we have both activity and structure.

Then the eighth perspective is pure activity (no structure) and this as such has no distinction between activity and structure, no slack in that sense, perhaps the decreasing sense. And so everything collapses into the nullsome.

Divisions [everything, anything] does [nothing, something, anything, everything]

- [{{Nullsome}} #] = everything does nothing

- [{{Onesome}} #] = everything does something

- [{{Twosome}} #] = everything does anything

- [{{Threesome}} #] = everything does everything

- [{{Foursome}} #] = anything does nothing

- [{{Fivesome}} #] = anything does something

- [{{Sixsome}} #] = anything does anything

- [{{Sevensome}} #] = anything does everything

Representations [being, becoming, acknowledging] does [taking up, acknowledging]

- [{{The}} beginning] = being does taking up

- [{{The}} end] = being does acknowledging

- [{{Understanding}} #] = acknowledging does acknowledging

- [{{Self-understanding}} #] = acknowledging does taking up

- [{{Shared}} understanding] = becoming does taking up

- [{{Good}} understanding] = becoming does acknowledging

Topologies [understander, understanding, understood, immersed] does [immersed, understood, understanding]

Secondary structures arise through various manifestations (determinations and nondeterminations) of the shift:

- determination of [{{{{Divisions}}}} division]:

- shift = 2 (outlooks - God's the beginning's unfolding, human's the end's coming together) x 4 (divisions)

- Operation +1

- Ambiguity: take a stand, follow through, reflect - the human condition - roles in the mind game

- Determine: the beginning (0) or the end (4). - representation of slack.

- Determine: +0, +1, +2, +3. - representation of nullsome.

- Outcome: (0, 1, 2, 3) or (4, 5, 6, 7).

- The division is in between, in the shift - it is the relationship from the whole to its parts. The division is either using the beginning (the nullsome) as a dummy variable and acting upon it with an operation; Or it is using the end (the foursome - which acknowledges the end and pulls the perspectives together) and then? considering it as the remainder?

- (For the coming together, consider each perspective as gaining a "marker" and then having a "marker for the markers" yielding 1+3+3+1. Or perhaps better - consider it an unloosening - first everything is held together, then it gets unloosened, decoupled, like dangling tassles.)

- Note: we may think of this as the ambiguity inherent in the threesome - the relevant structure. This ambiguity is given by the product of the two and the four representations.

- determination of [{{{{Representations}}}} representation]:

- shift = 3 shifts x 2 outlooks (why? involve human linearly or God cyclically)

- Operation +2

- Ambiguity: +0, +1, +2, +3. - representation of nullsome.

- Determine: take a stand, follow through, reflect - the human condition - roles in the mindgame

- Determine: the beginning (0) or the end (7). - representations of slack, increasing or decreasing

- Outcome: The threesome is either unbounded or bounded... (understander, understanding, understood) x (unbounded, bounded) = (God, God to other (God's will), God to God (life)) (other, other to God (wisdom), other to other (good will))

- looking out and back, back at one self - how does it seem from the side: human's view to God, God's view to human

- Note: we may think of this as the ambiguity inherent in the four representations that view the division through the kinds of relationships - understandings - between the beginning and the end.

- determination of [{{{{Topologies}}}} topology]:

- shift = 4 perspectives (each suitable as beginning or end) x 3 (members of threesome)

- Operation + 3 cyclic

- Ambiguity: the beginning (0) or the end (7). - representations of slack, increasing or decreasing

- Determine: +0, +1, +2, +3. - representations of the nullsome

- Determine: take a stand, follow through, reflect - the human condition - roles in the mindgame

- Outcome: Key concepts trigger the mind games...

- Note: this is the ambiguity inherent in the two representations that view the division through its wholeness - God (beginning) or human (end) - increasing or decreasing slack

- [{{Argumentation}} #]: nondetermination of division: 4x3 to 3x2

- [{{Verbalization}} #]: nondetermination of representation: 2x4 to 4x3

- [{{Narration}} #]: nondetermination of topology: 3x2 to 2x4

(Note the noncommutative definitions: 2x4, 3x2, 4x3 etc. and the role of x -1) Also, we get modes: +2, +1, +1, -1, -1, -2.)

Note that determination = ambiguity! So nondetermination is perhaps nonambiguity. Consider these identities as expressing the outlooks of the beginning and the end.

Determination: shift = perspective (shift of perspectives) Nondetermination: shift = shift (shift of shifts) ambiguity - a flip operation

So this is a sixfold expression of the shift.

God imagines the human outlook (of a three-cycle) by identifying himself (outside of us) with himself in the depths of our hearts. This is the way in which he is "alive" and we live in him.

The seventh perspective is what allows one to take up the perspective of another. It is in this sense that we have shared understanding. Perhaps the eighth perspective is what allows us to understand our perspective as just part of a larger perspective.

===Muddled thoughts===

Human allows for a unity of shifts - both his and God's. Human and God go beyond themselves together through shared understanding (back and forth).

With each shift of the threesome, God goes beyond himself into the human's world (the sixsome).

Pasidalinimas - bendrumas

See also: Shared

===What is Sharing?===

Sharing is:

- allowing for the referent, thus being one of the all who are of a one, thus for whom there is a greater ground and also a wider circle, so that they are open as a part in a whole, thus being among.

- And, not sharing is Or

===Related Concepts===

Sharing is a very central concept. There are many related concepts:

- God

- Referent, Reference, Grounds or Basis (a referent), Extent (all referents)

- Theory (what can be shared, the grounds for definition)

- BeingOneWith (sharing what can be shared, especially theory), NotBeingOneWith

- Truth (the extent of what can be shared), Scope

- Knowledge, Definition

- Undefined

- Unconditional, Conditional

- Coinciding (Defined as BeingOneWith)

- Agreement (Person), Basis for Agreement (Perspective), Basis for Disagreement (Position), Disagreement (System)

- Willingness, Nonwillingness

- God (Person and System), Human (Person and not System)

- Experiencing, Understanding

- DefaultPerspective (first shared and then defined), IndependentPerspective (first defined and then shared)

Scalar consequentialism

Kaip žaidžiu šachmatus: numatau siekį - ir tada mąstau, kaip aiškiausiu, saugiausiu būdu užtikrinti jį.

Šachmatai - scalar consequentialism - problema:

- nevertina kai kurių pavojų - nemąsto ilgalaikiais planais

- persistengia, nesirenka saugių pergalių, žaidžia per aštriai - doesn't draw the line - and if it did draw the line - would miss moves that flirted with the line

O žmogus planuoja, sumano, įžvelgia ir įgyvendina planus, keičia planus.

Šachmatų kompiuteris neskiria ar padėtis yra "lengva pergalė" ar "neaiški pergalė" - jis tik vertina "absoliučią persvarą". Ogi žmogui šis skirtumas labai svarbus.

Šachmatų kompiuterio žaidimo savybės gali nurodyti, kaip elgiasi birža ir kaip galima ją "nugalėti".

Strateginis planavimas (šachmatuose) - jeigu prasmingas - tai gali palaikyti strateginį planavimą ekonomikoje - pavyzdžiui, Airijoje.

Mes neturime laisvės kodėl, tik laisvę kaip; arba atvirkščiai, neturime laisvės kaip, tik laisvę kodėl; arba turime laisvę rinktis tarp šių dviejų laisvių.

Užrašai

- Intention important for morality, distinguishes actions.

- Normativity built into "not" - negation that define the representation of the nullsome.

- Degree of belief in X => the tendency to act on X.

Etika: Itin svarbi yra žmogaus vidinė būklė, jo "state of mind". Nuo to priklauso ar elgesys yra teisingas. Tai svarbu, ne pasekmės. Tik, aišku, mes negalime spręsti apie žmogaus vidinę būklę. Bendrai, tik jis pats vienas gali spręsti, arba jį mylintis žmogus. Šį klausimą išreiškia abejonė, Ar tai iš tikrųjų protinga? ir dvejonė, Ar įstengiu svarstyti klausimą?

Neteisk ir nebūsi teisiamas: Kiekvienas teismas yra tuo pačiu teisėjo patikrinimas, ar jis teisingai teisia. (Prisimenu World Bank konkursą.)

What do you want? Do people know?

3 galios: žinojimas, garbė, turtai - iš Platono Valstybės. Šališkas teisėjas - protavimas sprendžia, tad jisai šališkas žinojimui.

Dorovė

Troškimai, poreikiai

- Desire is related to needs?

Gyvenimo žaidimas

- Dorovė: Games should reflect our real desires rather than having our wishes match the game. This is the basis for moral feelings: Expectations not matching up to our wishes is the basis for worldmaking, the boundary of self and world.

- Morality -> are we dictating the game based on reality - keeping it tentative? Is the game taking over?

Tiesa

- Good - slack gives room for contradiction, for self-correction. Truth is that contradiction. Thus good and truth make for the finest grained grid of gaps.

Kompiuteriams išsiskiria elgesys ir dorovė

- Computer with bugs? (Have the slack to) make mistake -> about self -> about world.

- Computers having intentionality (desires) will have the dilemma of implementing immediately (but with errors) or waiting (and lacking).

Pagarba

- Dorovei svarbu gerbti atjautą, savo ir kitų. (Pavyzdžiui, žydams) Lygiai, kaip svarbu gerbti jusles, savo ir kitų. Gerbti liudytoją.

Dorovės mąstytojai

- Mencius: Žmonės daro blogą nes jie priversti taip elgtis. (Panašiai kaip vanduo priverčiama kilti aukštyn, nors bendrai jisai teka žemyn.)

- Mind-heart, nature, heaven. Mencius.

- Tasan - sympathy as commiserating mind-heart.

- Peter Unger Atsakomybė už kitus pasaulyje.

- Martha Nussbaum. Practices of just, fair and right.

Prigimtinė teisė: Natural law

Tu mano vaikas, tad tu, kaip mano Sūnus, supranti viską aplinkybėse, o aš už aplinkybių. Tad įsakymai derina mūsų santykį. Mano Sūnus išsako koks tu turėtum būti, o tu esi toks, koks gali būti. Tad įsakymai sulygina tave ir mano Sūnų, kuris jų ir laikosi, tiek teigiamų, tiek neigiamų. Tad domėkis jo pavyzdžiu. Jis gyvena manimi, man visaip atsidavęs, tiek kūnu, tiek protu, tiek širdimi, tiek valia Jis visur man pavaldus, mane priima kaip gyvenantį plačiau už jį. Jis taip pat neigiamais įsakymais gerbia ir myli jus kiekvieną, palaiko jūsų erdves, tai ir yra šitų įsakymų pagrindas, kaip esi pastebėjęs, tad ištirk mano meilę jums, kartu ir jam, kaip ji deri su jo meile jums taipogi. O tai, kad kiekvienas atsako pirmiausiai už save, taip pat už vienas kitą, o manimi už visus. Tu suvoksi, kai ištirsi.

Aš jus sukūriau, jūsų vienumą ir būtent jūsų paskirumą, tai labai susiję, ir tą santykį išsako mano įsakymai. Pirmi keturi įsakymai, tai mano troškimai, tai mūsų troškimai, mūsų vienumo pagrindas, tai įsakymai būti viena su manimi. O kiti šeši įsakymai tai mano įsakymai jums būti viena su kitais, kitame įžvelgti mane, mano tolydumą pereinant iš jūsų bendrumo į paskirumą, kad esu tas pats Dievas, tai jum tenka tą tapatumą gerbti, jo laikytis, jį išlaikyti. Taigi, esate atskirti kūnais ir protais ir širdimis ir valiomis, tad nežudyti, tai gerbti visų kūnus, nevogti ir nesvetimauti, tai gerbti visų protus ir susitarimus, nemeluoti ir negeisti daiktų bei žmonių, tai gerbti visų širdis, visų lūkesčius. Tai yra troškimai, o tuo pačiu reikia gerbti netroškimus, gerbti pasaulio tvarką, gerbti paskirų žmonių prisirišimus, ir gerbti kūrybos galimybes, taigi, gerbti kaip paskirai yra, kaip paskirai prisiriša, kaip paskirai galėtų dar būti. Tad įsakymai įvairiai sieja troškimus ir netroškimus. Tu vis mąstyk, tu išsiaiškinsi.

Kaip tu žinai, mano troškimai yra vienumo pagrindas. Juk troškimais sutampa tai kas galėtų, turėtų būti ir kas yra. Troškimais išsipildo. Tad troškimai sieja dorovę ir elgesį. O netroškimai atskiria dorovę ir elgesį paskirumu, nevienumu. Tad ieškok vienumo įsakymuose. Ir kaip matai, yra prisirišimo laipsniai. Vienas laipsnis - tai priimti viską kaip yra - nežudyti, nevogti, negeisti daiktų. Kitas laipsnis - susitarti su kitais - gerbti jų troškimus - nesvetimauti, negeisti kito mylimojo - trečias laipsnis, laisvai kurti - nemeluoti - būti viena su savo mintimis, su tiesa. Kūnu priimi kaip yra, protu susitari kaip galėtų būti, o širdimi išjauti, kaip dera. Ir gali troškimų ir netroškimų santykyje ieškoti ryšio tarp šešių porų keturių lygmenų ir trijų porų pertvarkymų.

Aš tave laiminu. Tu ieškai manęs, tu mano vaikas, kad aš atgręščiau tave į kelią kuriuo einu, į savo nežinomybę į kurią eisime ir einame kartu, tavo žinojimu ir mano nežinojimu, juk tu eini pirma manęs ir tu manęs lauki, kaip mano mokytojas. Tad tas laukimas manęs ir į permainas, tad suvok kaip ir kur iškyla kantrybė, tiek lūkesčių įtampoje, tiek abejonių nerime, tiek galimybėje rūpintis kitų poreikiais. Tad būtent septintu požiūriu plėtojasi dorovė tad ieškok ryšių tarp šių elgesio sluoksnių, tarp valios vertybių ir jo svertų, taip pat širdies lūkesčių, jos svertų, ir proto abejonių, jo svertų, ir kūno poreikių, jo svertų ir būtent tais svertais galiausiai tuo tarpu laukiame. Tad ir tu lauk ir suvok kaip tas laukimas vyksta ir bręsta, kaip juo dorovė yra galimybė, kaip šešerybe išgyvename tą laukimą, o elgesys tėra dorovės išvada. Tad visa laisvė yra būtent dorovėje, tačiau jums atrodo atvirkščiai. Šį apvertimą sudaro esmę visų požiūrių permainų. O požiūriai yra tas išėjimas į laukimą ir sulaukimą.

Dorovė:

- dorovė išplečia gerumą trimis sąmoningumo laipsniais. O tai vyksta lyginant skirtingus lygmenis, skirtingas aplinkybes, ir tiek sutelkiant dėmesį, tiek pripažįstant kas už jo.

- elgesys ir dorovė išplaukia iš meilės, tad suvok meilę, kaip mano esmę, kuri esminga kiekviename išmanyme ir tą išmanymą padaro pilnaverčiu.

- ...Tad ieškok šito ryšio ir suprasi šešerybę bei dorovę.... Aš laiminu visaką. Viskas išplaukia iš manęs ir ne vieną kartą, o trimis lygmenimis, tiek mano, tiek Sūnaus, tiek Dvasios kampu. Tad turi būti kiekviename lygmenyje esmė to mano išėjimo už savęs, o ta esmė yra meilė. Tad mano vienumo esmė yra meilė sau, asmens vienumo esmė yra meilė vienas kitam, o asmenų vienumo esmė yra meilė visiems. Tad mylintysis yra mylimojo vienumas ir jumis, jūsų trejybės ratu, tas mylintysis yra vis tas pats, nes meilė lieka ta pati, tik keičiasi jos palaikoma gyvybė, ir tos gyvybės esmė - valia, ir jos santykis su mano valia, kurį vis kitaip išsako paklusnumas, tikėjimas ir rūpėjimas.

- ...O tai ir yra dorovė, besąlygiškumo sąlygos, tad ir įsakymas mylėti. ...Meilė tampa įsakymu nes aš noriu ištirti ar ji besąlygiška, ar jos gali laikytis, ar ją gali puoselėti tie, kurie patys sau nėra išeities taškas, tie kurie laisvi, kurie gali tiek mylėti, tiek būti mylimi, tiek nemylėti ir nebūti mylimais. Tad mylėk ir suvoksi, jog mylintysis irgi nori būti mylimas ir mylimasis nori mylėti, nes meilė yra nesiribojimas savimi, tad ir kartu su laisve tarp mylimojo ir mylinčiojo atsiranda ir ją papildantis įsakymas visaip mylėti, ne vienaip ar kitaip, o vis visaip. Tad meilė yra visapusiškumo, besąlygiškumo pagrindas.

- ...Tai ir yra pasirinkimų malūno ir visos dorovės esmė, paaiškinti iš kur meilė kyla, kaip jūs išeinate už savęs, ogi todėl kad taip yra paprasčiausia mylėti tave mylintį, galiausiai mylėti visus, juk paprastumas laimi, užtat tiesa viską išveda ir atskleisdama mane, juk aš ir esu paprasčiausias. ... Žmogus yra mano mylimas, bet jis nebūtinai mane myli ar pažįsta. Jis dar nesusigaudo, jog jisai yra mano vaikas. Tad jis nebūtinai vykdo mano valią. Ši jo laisvė ir yra pasirinkimo malūno pagrindas grindžiantis jo pažinimą savęs ir susigaudymą, nuklydimą ir pasitaisymą, jo atsirinkimą mylėti, vietoj kad nemylėti, o jį tam pamoko grožis-žavesys ir artimumas, jį pamoko aidai, juk aidai ir yra meilės sandara, juk jinai papildinys. Tad mylėk ir suprasi iš kur meilė kyla ir kuo ji laikosi ir į ką atsiremia.

- ... Tad žmogus ir yra amžino gyvenimo sandara, tai ir yra dorovė, tai žmogaus sandara, šešerybė. Tad suvok žmogų, kaip jisai suveda mano šokį, kaip jisai nepriklausomas nuo įtampos tarp manęs ir Sūnaus, kaip jį papildau tiek Dievu, tiek gerumu, būtent dvasia, tad jį myliu. ... Žmogus yra mano vaikas. Jisai gimsta padalinimų ratu, o jį išbaigia žmogus, kaip sandara, į jį susiveda visi padalinimai ir už jo, be jo lieka tik aš ir gerumas. Tad žmogus yra ir susidaro iš viso to, kas skiria mane ir gerumą.

- Dievas gyvena mumis amžinu gyvenimu, visu tuo, kas tarp Dievo ir gerumo: Žmogus, tai mano vaikas. Kaip žinai, jisai gimsta man pasitraukus ir naujai iškylant Sūnumi, tačiau jisai turi susigaudyti, jog yra Dievas, o tuo pačiu dar tai priimti, taip gyventi. Tai ir yra dorovė, to vaidmens priėmimas. O susigaudymas, tai žmogaus būklė, tai amžinas gyvenimas, taip kad manasis dieviškumas jumis atsiskleidžia amžinybės mastu būtent amžina branda. Būtent jūs amžinai bręstate ir aš jumis, tai mano kelias, kaip Sūnus kalbėjo, kelias, tiesa ir gyvenimas, esate jūs, yra Jisai, tai mano kelias, ir būtent aš jumis einu, todėl tuo ir gyvenkite su manimi ir priimkite tai. Tai ir yra dorovė, šešerybės išsakyta, tai jūsų dvasios sandara kurią papildau savimi ir gerumu, tuo jus įprasmindamas ir įkvėpdamas savo dvasia, be kurios tesate sandara.

- Ieškok trejybės ir jos ištakų, ieškok šešerybės ir jos atvaizdų, tai žmogaus pagrindas, jo elgesio ir dorovės taipogi. Aš jumis gyvenu būtent sąmoningumu, tad pirmiausiai trejybe ir paskui šešerybe, toliau vienybe ir ketverybe ir septynerybe ir dvejybe ir penkerybe, tad ieškok manęs šia tvarka, ieškok sąmoningume.